3 Name Problem

How do you tell the true story of a group of people who keep changing their names?

I’ve spent years writing about the history of the BBC, and got pretty used to its abbreviations and insider terminology. ‘BH’ for Broadcasting House; ‘DG’ for the Director-General; ‘the Nations’ for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Whole divisions have become associated with the buildings which house them. For years ‘the World Service’ and ‘Bush’ have been fully interchangeable. When I worked for the Corporation in the late-1980s and early-1990s, I got an instant introduction to the jargon of the professional broadcast journalist: ‘sitrep’ for ‘situation report’, ‘disco’ for a studio discussion.

As I researched the Second World War, things got a bit trickier. Security demanded secrecy. Nick-names and code-words kept popping-up. The Corporation’s main base outside London – home to Monitoring and a large number of programme-makers, somewhere supposedly hidden from prying enemy eyes – was Wood Norton Hall near Evesham. If staff referred to it among themselves, it was in the guise of ‘Hogsnorton’.

[BBC wartime Monitors at work at Wood Norton. Image: ©BBC]

So when I switched recently to researching the history of Britain’s wartime propagandists, I really should have been prepared. Anything that touches on the world of intelligence and deception is bound to get murky. The most obvious examples – and therefore the easiest ones to get one’s head around – are the names, and the cover-names, for the main government agencies. MI5 is the ‘Security Service’. MI6 is the ‘Secret Intelligence Service’.

So far, so good. But while the former’s existence was publicly acknowledged at the time, the latter’s existence certainly wasn’t. Wartime records might occasionally refer to ‘S.I.S.’, but more often than not, we just find opaque references to an anonymous Whitehall department of one kind or another. And soon enough, when dealing with both MI5 and S.I.S., you find yourself sifting through a multitude of cover-names and cover-addresses: ‘Passport Control’, ‘Our Man in…’, ‘C’, PO Box 500, Room 055, St James’s Street, Wormwood Scrubs, Blenheim Palace, ‘Town’, ‘Country’.

‘Town’ and ‘Country’ was a major distinction for the propagandists, too. For much of the war, those charged with waging the battle for hearts and minds in Nazi Germany and occupied Europe, were gathered together either at Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire – ‘known simply as Country’ – or at Fitzmaurice Place, and later Bush House, in central London – ‘Town’. But the picture’s more complicated still, because the question of whoexactly they said they were working for kept shifting – and not always in line with the name of the organisation that formally employed them.

At the start of the conflict there was ‘Department E.H.’, a propaganda department named after a building in London, Electra House, which once – but no longer – housed it. Department E.H. was in some obscure way linked to the Foreign Office or, more specifically, the ‘Political Intelligence Department’ of the Foreign Office. The P.I.D. was not quite the same as ‘E.H.’, but to make things messy E.H. often used P.I.D. as its cover name.

In 1940, Churchill’s new coalition government created the Special Operations Executive – the S.O.E. – which supposedly brought together sabotage operations and propaganda. In practice, the S.O.E. was split into entirely separate units. ‘S.O.1’ dealt with propaganda, ‘S.O.2’ with sabotage. Those who’d been employed by Department E.H. now worked for S.O.1 – though usually carried on referring to ‘E.H.’ The following year there was another reorganisation, and S.O.1’s work was hived off and absorbed into the newly-created Political Warfare Executive. The P.W.E., like S.I.S. was not publicly acknowledged: formally, it did not exist. The old Political Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office was therefore used as a cover name. Some documents would just refer to ‘the Executive’. But then there was also a ‘Security Executive’ which brought together the heads of the various civilian and military intelligence agencies. So which one did they mean?

The fun really starts when we get to the people themselves.

The BBC’s wartime European Service might have been dedicated to disseminating the truth, but any émigré who broadcast to Nazi Germany or occupied Europe from London had to think carefully about whether they wanted their real identity to be known, especially if they had family back home. The BBC also feared that Hitler’s own deeply antisemitic propagandists would take any opportunity to condemn British broadcasts for being nothing but the voice of disgruntled Jewish exiles. So, exiles – and the wartime BBC employed many hundreds of them - were generally kept away from the microphone and confined to backroom roles. Identities were also blurred. Some had been in Britain for years and already adopted a new name; others would only be naturalised after the war. Whatever the reason, it means that the exiled Austrian journalist Robert Ehrenzweig has to be traced in BBC records as Robert Lucas. The Hungarian-born and Viennese-educated Julius Pereszlenyi, who also worked for the German Service, was – and remains - better known as Martin Esslin. Their British bosses – people like the Head of the German Service Hugh Carleton Greene, or his star commentator Lindley Fraser – were allowed to keep their own names on air. After all, there was no pretence that the BBC was anything other than the Voice of Britain.

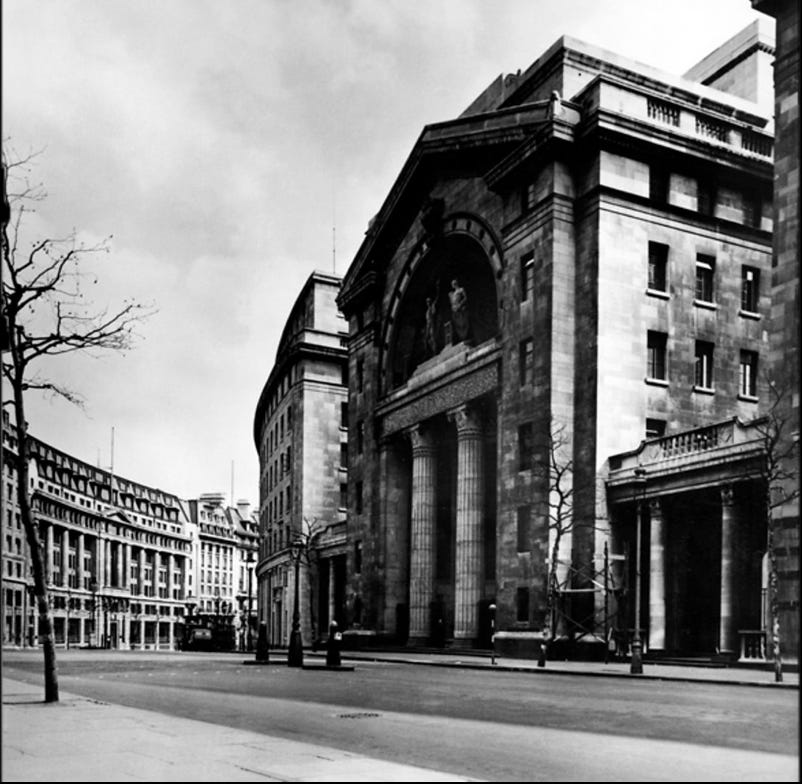

[Image: Bush House, home of the BBC European Service from 1941. Image © BBC]

Occasionally, though, even a genuine British identity presented difficulties. When the young English actor Marius Goring joined the German Service in 1941, it was thought his name sounded far too similar to that of the head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Goering. Listeners in Germany got to know him as ‘Charles Richardson’.

For those propagandists employed directly by the P.W.E. out in Bedfordshire, running a series of so-called ‘black’ radio stations designed to spread disinformation to the enemy, secrecy could reach truly surreal levels. If they were to maintain the pretence that they really were renegade German stations broadcasting from inside Germany – and to keep that pretence going for the entire length of the war - obscurity was paramount. Identities – both native and émigré, for those performing in front of the microphone and those behind-the-scenes – had to be blurred.

Theis meant that the moment they arrived at their countryside residences, everyone was told never to use their real names – or even give anything much away about their previous lives. One of the P.W.E’s star presenters – pretending to be a disgruntled and rather foul-mouthed army officer of the old school, was known on air as ‘The Chief’. Among colleagues he was ‘Corporal Paul Sanders’. His real name was Peter Secklemann. There was also Franz Josef Leuwer, who colleagues simply referred to as ‘the Sergeant’ and who, when naturalised as a British citizen in 1946, became Frank Lynder. The former German diplomat Wolfgang von Putlitz was introduced on his arrival as ‘Mansfeld’ and later became known as ‘Mr Potts’. The Social Democrat politician Max Braun was ‘Mr Simon’. His brother Heinz was ‘Mr. Forster’. Somewhat perversely, anyone whose real identity happened to sound rather too British to begin with would be granted a German name. For the duration of his secret wartime service to the Allies the anti-Nazi Otto John therefore became ‘Oskar Jürgens’.

As is often the case, it’s the women who prove hardest to trace. And there were plenty of talented and important women at the heart of Britain’s black propaganda machine. Unfortunately, most accounts of Britain’s black propaganda operation have been written by the men in charge. So from Sefton Delmer we get tantalising, and, of course, horribly infantilising, references to Franz Leuwer’s anonymous ‘girl research assistant’, or to the team of ‘girl secretaries’, or the ‘graduate girl researchers’ who worked in Woburn Abbey’s intelligence department – a department that just happened to include, among others, the young Muriel Spark.

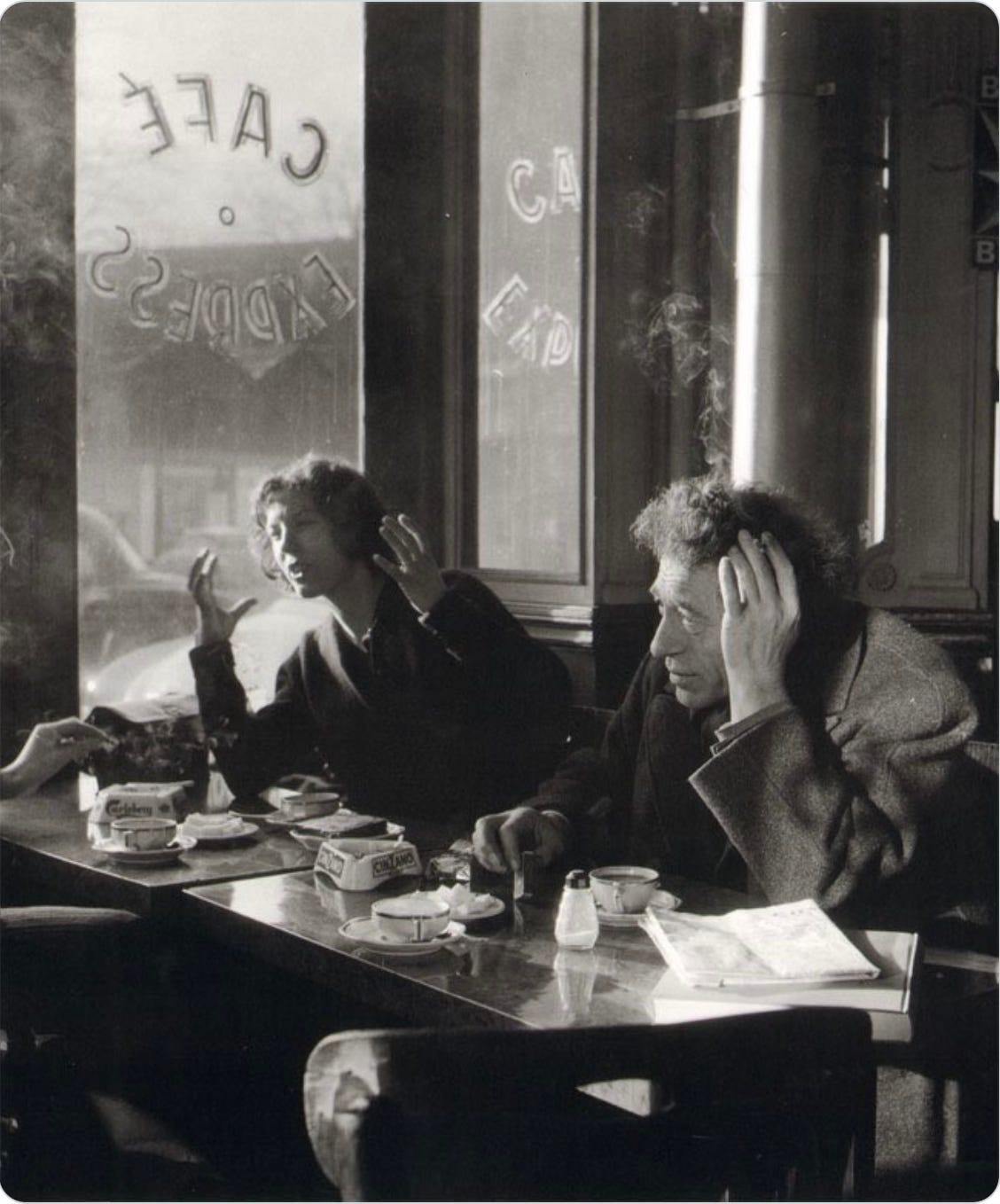

[Isabel Nicholas/Delmer/Rawsthorne in Paris with Giacometti]

Even when they are named, these women’s full contribution is pushed just beyond our normal field of vision. As researchers we have to keep glancing left and right to see them in the round. ‘Mrs Delmer’ has been passed down to us as ‘Housekeeper’ for the small team of broadcasters that her husband Sefton led as ‘Housemaster’. But she’d grown-up – and made her name as a muse of Giacometti (and an artist in her own right) – with the name Isabel Nicholas. And after the war she would achieve further acclaim for her art as Isabel Rawsthorne. Even ‘Isabel’ with an ‘a’ occasionally mutated into ‘Isobel’ with an ‘o’. It’s only by pursuing all these identities that we can start to ask the right questions about what she got up to in those middle years of her life in the Bedfordshire countryside.

But if I had to point to the single, most complicated identity of all it would be that of a former SS officer who was smuggled into Britain in 1943 to work for one of the P.W.E.’s fake radio stations. I won’t reveal his full story – for that you’ll have to wait for my next book. But it is both extraordinary and – because of his rapidly shifting identity – almost impossibly complicated to unravel.

[Image: the photo of our ex-SS officer in a passport provided by MI5]

In his account, Sefton Delmer uses just one name. In fact, he had two German names – one apparently his real name, the other he used while on the run from the Gestapo. When he arrived in Britain, the Security Service gave him a Swedish cover-name. But since he was an informer, MI5 also allocated him a code-name, as they did with other agents on their books.

Not so much a 3 Name Problem, then, but a 4 Name Problem. It’s a researcher’s nightmare. But also, since I love history when it turns into a detective story, a researcher’s dream.

*************************************************************************************************************

Thank you for reading my Substack. I intend to publish a new essay fortnightly – usually on a Thursday. The next one will probably include some thoughts on what I’ve been reading, watching, and listening to recently. So please ‘keep tuned’, as they say.

I must say I'm enjoying these musings of yours, David. And really looking forward to the next book. Though it's not really like the need to keep a foot on the ground when taking that long shot at the billiard table (using the awkward long rest), I can see how you need to lift your eyes to what's going on around you - and not let it pass unremarked on.