Bronowski Beat

Jacob Bronowski's epic 1973 TV series 'The Ascent of Man', a troubled broadcasting career, and MI5 interference in the BBC

It was published in 1974, so I think it must have been for my twelfth birthday that I got given a copy of The Ascent of Man by Jacob Bronowski. I must have been a little bit nerdy even then, though I suspect that I didn’t really take much of it in. I have a vague memory of holding it in my hand while lying inside a tent on a family holiday somewhere cold and wet.

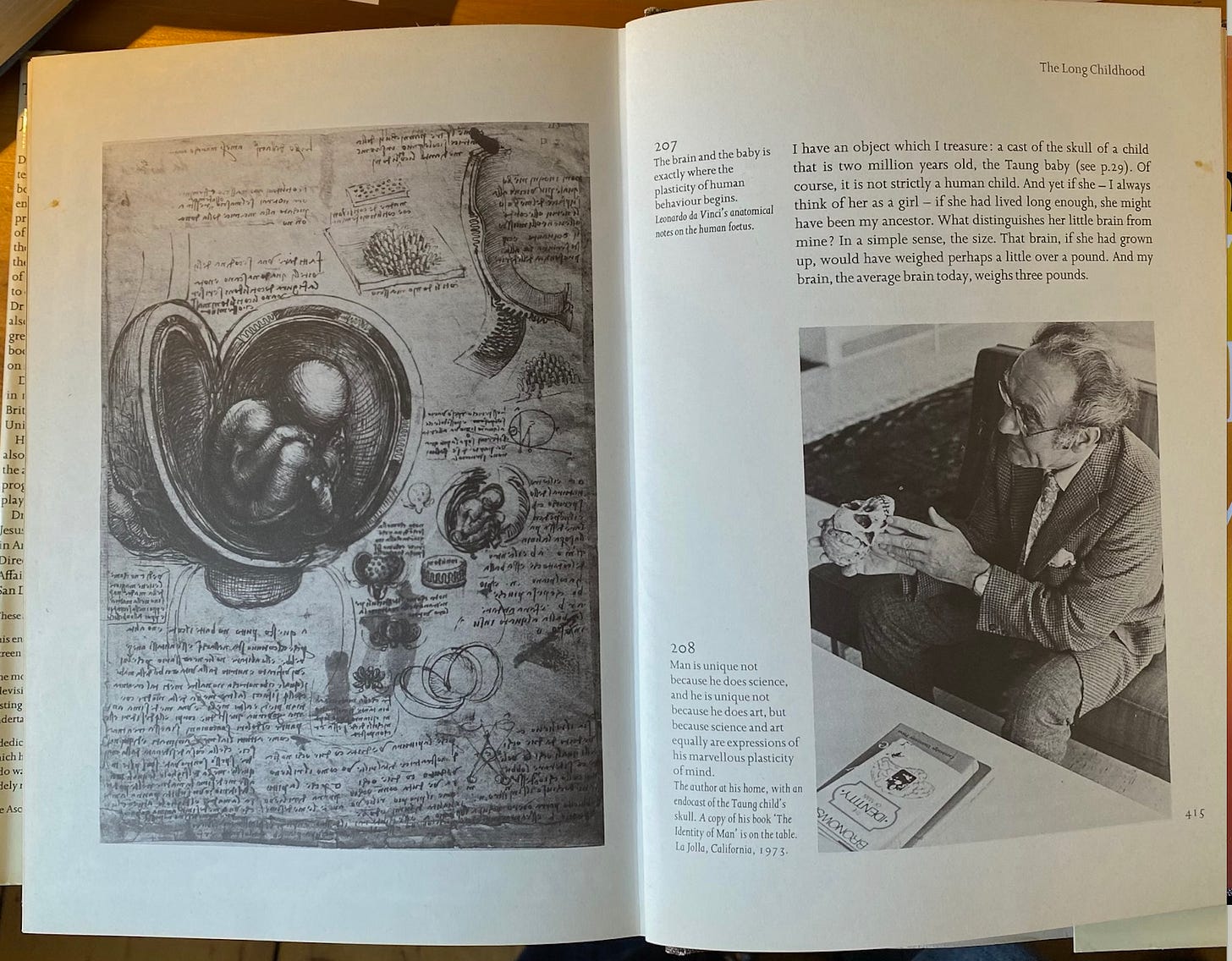

I’m flicking through the pages, absorbed more than anything by the pictures: Impala grazing on the savannah, an Australopithecus skull, the prehistoric art at Altamira, long exposure photographs showing the trajectories of the planets. And, of course, there was Bronowski himself: short, bespectacled, bushy-browed, receding – the very picture of ‘The Distinguished Intellectual’ which, perhaps even then, I aspired to be when I was a grown-up.

What sent me spiralling back fifty years was an email which landed in my in-box in June. It was from the BBC Radio producer Martin Williams.

In his message, Martin told me he was putting together a Radio 4 programme about Bronowski. It would mark the anniversary of his death, which came – suddenly and shockingly early – just one year after the television version of The Ascent of Man had been broadcast.

Many regard the series as one of the finest television documentaries of the last century. Certainly it was one of the most influential. It was conceived in part as a riposte to Kenneth Clark’s epic Civilisation, which, when it was broadcast on the BBC four years earlier in 1969, had established the template for sumptuously-filmed, globe-spanning, multi-part televisual essays presented as personal views by rather grand figures who ‘knew their stuff’. Quite apart from its now rather archaic focus on the achievements of High European art, Clark’s Civilisation had neglected to include science in any of its 13-episodes of human history. The BBC’s powerful head of ‘TV Arts, Science and Features’, the cigar-smoking impresario-like figure of Aubrey Singer, was sufficiently outraged by this omission that he immediately invited Bronowski to write and present another 13-part blockbuster that would redress the balance.

It was a good choice. Although Bronowski was a scientist, he’d published poetry when he was a student at Cambridge. He’d written a book about William Blake. More pertinently, he’d also spent years attempting to bring together the ‘Two Cultures’ of arts and science. For him, scientific thinking was one of those things that introduced new ideas into culture, while it was through leaps of imagination and foresight– those extraordinarily human skills – that scientists also think through a problem. By weaving together science, literature, anthropology, and philosophy, Bronowski would use The Ascent of Man to show how, over thousands of years, this subtle interchange gradually made us who we are.

Bronowski’s argument builds carefully and cumulatively through each 50-minute episode. The whole series is up on BBC iPlayer, and I’d recommend catching it while you can.

But there is one episode in particular – episode 11, Knowledge or Certainty? – which became a celebrated moment of TV history, a kind of ur-meme. The BBC itself knew the episode had a peculiar force of its own even before the series was aired, since it was an episode they chose to screen at their lavish press launch.

In Knowledge or Certainty? Bronowski traces some of the great discoveries in twentieth century physics, and shows us how their greatest achievement was to suggest that there’s no such thing as absolute certainty, just multiple ways of understanding something – that our understanding should be a composite of viewpoints and should be constantly evolving.

Towards the end of the programme, we see him at Auschwitz, where members of his own family had been murdered in the war. He stands with his feet at the edge of a pond. It is where the ashes of the dead were once tipped, and where the water still holds onto its grim material legacy. ‘There is no absolute knowledge,’ he tells us, ‘and those who claim it, whether they’re scientists or dogmatists, open the door to tragedy.’ Then, unrehearsed, he steps forward – hesitantly – kneels down, and scoops his hand into the water to bring up the muddy remains. The picture slows and then freezes.

It’s a moment that captures the essence of Brunowski’s warning about the dangers of dogma – where the search for a ‘final solution’ to something might lead us. So I suspect that Martin’s Radio 4 documentary, The Ascent of Jacob Bronowski – broadcast under the Archive on 4 banner at 8pm, Saturday 17 August – will linger a while on this particular section of the 1973 series. But knowing Martin and the kind of programmes he makes – always adding some wonderful radio poetry to the mix – the programme will also allow his presenter, Frances Stonor Saunders, to explore, obliquely, all sorts of other resonances. Do have a listen.

The Ascent of Jacob Bronowski, BBC Radio 4

My own small role in Martin’s programme was to say a few words, not just about that episode at Auschwitz, but about Bronowski’s broader BBC career. It led me into taking a brief dive into his life story, and, in particular, to having to read several hundred pages of some truly extraordinary documents belonging to the Security Service which are now held at the National Archive.

Until I did this, I hadn’t appreciated Bruno’s deeper – and really rather troubled - history with the BBC. Nor his entanglements with MI5, which had him under surveillance for years.

His daughter, Lisa Jardine, suggested that it was this surveillance – and the misunderstandings it created – that damaged his broadcasting career in the 1950s and 1960s.

MI5’s monitoring of Bronowski began just over a month after Neville Chamberlain had made his famous declaration of war against Germany on the BBC Home Service – a time when the whole country was on high alert.

On 18 October1939, a schoolteacher in Yorkshire contacted the Security Service suggesting they take an interest in someone he’d come across called ‘Jacob Bronowski’. This man, the schoolteacher told them, was ‘extremely left – and has no hesitation in reviling his country’. MI5 were sufficiently intrigued to ask Special Branch in Hull to keep an eye on him. And Bronowski, a talented and highly promising mathematician then lecturing at the local University, certainly provided plenty of opportunities for the local officers to get their investigative teeth into. When not teaching, he would give talks at the local Left Book Club or the People’s Theatre Guild – about the civil war in Spain, the need to support refugees, the need to build a more equal society in German after it had been defeated, the exploitative underpinnings of the British Empire. On one occasion he read one of his own poems, How I Hate War.

There’s no sign in these reports of Bronowski preaching anything particularly revolutionary or in the slightest bit threatening to the British state. But for a Special Branch clearly all too ready to dismiss anyone with even vaguely left-wing views as a Fellow Traveller, he was damned by association. There were Communists in the audience, as well as what Hull Special Branch recorded as a ‘noticeable percentage of Jews’. Audience members were described as ‘Bronowski’s political disciples’, as if he was the leader of a dangerous cult. By January 1941, those following him had concluded that ‘Bronowski is a Communist in everything but name.’

This was a judgment that failed to catch the subtlety of his politics. It’s true that his mother and sister were both active Party members, but ‘Bruno’ – as everyone who knew him called him – never joined up. He was certainly a socialist. For him, science and socialism both offered the hope of a better life – something fuller, richer, larger. On the whole, though, he was less interested in proletarian revolution than in secular modernity. He wanted to do his bit to ensure the continuation of Enlightenment liberalism.

But in MI5 documents, sentences, once typed up, have a habit of becoming unimpeachable. They’re repeated and given new life. Someone contacts MI5 to make an enquiry. Then someone in the Security Service’s office registry reaches for a personal file. They’re looking for a ‘trace’, that passing reference of suspicious behaviour in the past. And there it is, now fully sedimented into eternal accusation. And those eight words – ‘Bronowski is a Communist in everything but name’ – are destined to haunt Bruno for the rest of his career.

The words first come back to bite in 1943, when the government is keen to use his mathematical skills for secret war work.

The ‘trace’ of Communism meant he was blocked at first, though, in the end, such was the importance of the job required – calculating the radius of damage caused by the RAF’s bombs being dropped over German cities – that the Ministry of Home Security decided to look the other way and take him on. By 1945, he was out in Japan, assessing the damage done by the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A year later he was on the BBC for the first time. The Americans had conducted a nuclear weapons test at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific: Bronowski was invited to talk about it, drawing on his previous experience of the destructive power of the bomb.

Over the next decade he became a household name through his many polymath turns on radio and television – most famously as a regular panellist on The Brains Trust. But ever since his visit to Japan, he kept wanting more than anything to come back to that theme of atomic power – its uses and misuses. On nuclear technologies, he once said ‘Like every great discovery, they offer an equal potential of happiness or disaster.’

So it should have come as no surprise that when the BBC contemplated a TV series about atomic power, they reached out to Bronowski as the man to present it. It was 1955, the height of the Cold War, and Bronowski had spoken very publicly against the proliferation of nuclear weapons. When it came to atomic energy, though, he was at the very least open to persuasion about its benefits. And, of course, there was that underlying principle that he held dear: uncertainty should always trump dogma.

Planning for the series got underway, and the producer, Grace Wyndham Goldie, spent many hours with Bronowski sketching out a detailed programme running-order. But then, come the summer, everything went quiet. Bronowski tried contacting the BBC. Everyone seemed busy, distracted. There was a General Election to cover in May. ITV was going to be launched in September and the BBC was jittery about how it would have to respond. Still, the silence was ominous. Bronowski persisted, wanting an explanation. Eventually, Grace Wyndham Goldie got back to him. Apologies … things had moved on … plans had been revised … a different programme was now in prospect … a different presenter, too… .

Quite rightly, Bronowski was furious and demanded an explanation from the top. BBC executives went into a huddle. They tried to find out what had happened – and when they did, they admitted to each other that they would not be able to tell Bronowski the real reason for him being abandoned.

In fact, in April, the person in BBC Staff Administration whose job it was to monitor any security concerns with staff, Norah Wadsley, had tipped off MI5 about the series – asking them if Wyndham Goldie should be told that Bronowski was someone of ‘concern’. Wadsley had spent most of her career in total ignorance of the scientist’s political past: the BBC had used him repeatedly and there had never been any suspicion that he was abusing his access to the airwaves to proselytise for Communism. But then in 1953, MI5 had seen fit to hand the BBC a copy of their files. And there were those words again, ‘Bronowski is a Communist in everything but name.’

Exactly what happened next behind the scenes remains something of a mystery – although the Radio 4 programme will, I suspect, attempt to unravel it a little. What we do know is that MI5 tipped of the Atomic Energy Authority about Bronowski’s involvement in the BBC series – and the Atomic Energy Authority declared Bronowski persona non grata. Though MI5 had never instructed the BBC what to do – that wasn’t their style – it had clearly become impossible for the broadcaster to proceed with the series.

It wasn’t the end of Bronowski’s broadcasting career – although he was sufficiently upset to spurn the BBC’s approaches for several years. But it is one of the clearest examples I’ve come across of MI5 interference with the output of the national broadcaster, and it could so easily have proved fatal to Bronowski’s future career as a public intellectual. It makes the very existence of that epic 1973 series, The Ascent of Man, even more miraculous than I previously thought.

Wow: some tale

I'm so glad that "The Ascent of Man" was made and broadcast. It was an incredible series. This is the first time I have read of his background leading up to it. Thanks for writing it.