Humanising History

What might a treasure-chest of hitherto unseen and unheard interview recordings tell us about events we think we already know inside-out?

A multitude of unsolicited emails poured into my old university email account this week. Some invited me to have an article published in a Not-Very-Well-Known journal about biochemistry. Others dangled before me the promise of keynote speaker status at a conference about aeronautical engineering in Bali. All involved a spectacular down-payment in advance.

Among the detritus, though, was one genuinely intriguing offer. Would I like to interview Britain’s oldest living Spitfire pilot?

Jack Hemmings is 103 years-old and lives in Kent. During the Second World War he engaged in dogfights with the Luftwaffe over the South Coast, though he spent much of the war in India and the Far East. Later, he flew on humanitarian missions in central Africa, delivering medical aid and providing emergency evacuations for refugees. It was a charity he’d long helped – Mission Aviation Fellowship – that was now reaching out to me.

I was a little perplexed about this at first. Jack sounded amazing. Obviously, it would be wonderful to meet him. But why me? I’m not a military historian; honestly, I know next to nothing about aeroplanes. As an interviewer, I’d be useless.

As it turned out, Jack’s contact from the charity had spotted an article I’d written for the BBC about D-Day back in 2019. I imagine she was trawling the Internet for relevant material to help mark the 80th anniversary of D-Day next month. My own piece wasn’t a regular slice of militaria: I’d been looking at how the BBC covered the whole event. We might know a great deal about what was broadcast on the day, but I felt there was little information in the public domain about what went on behind-the-scenes. I was interested in the hidden labour involved when Britain’s national broadcaster committed itself for the first time to large-scale, real-time coverage from the battle-front.

In telling that story, I collected material from the BBC’s voluminous written archives. I also had privileged access to the back-catalogue of programme recordings. But the central thread of my piece drew on one particular priceless historical resource that was – at least, when I wrote the article – firmly under lock-and-key at the Corporation and still not accessible to any other historian: the BBC’s own in-house oral history collection.

I want to tell you a little more about this collection, because I think it’s both fantastically interesting and still almost entirely unknown, even though it’s now fully accessible – for free, for anyone, from anywhere in the world. I think it offers a vivid, intensely personal way of exploring the social and cultural history of the twentieth century.

*

What exactly is the BBC’s oral history collection? It’s an archive of more than four hundred interviews with former members of BBC staff – Directors-General and departmental heads, journalists and presenters, engineers and studio directors.* They started to be recorded in 1973, just after the BBC marked its 50thanniversary. They’re still being added to fifty-one years later.

Among the six hundred and fifty plus hours of tape, there’s David Attenborough talking about joining the Corporation as a young man in the 1950s, making his early wildlife programmes, being in charge of BBC-2 in the 1960s, dealing with Anthony Eden during the Suez Crisis. There’s John Snagge recalling the General Strike in 1926, and Cecil Madden on the very first television transmissions from Alexandra Palace. There aren’t nearly enough women in the collection, but there’s Grace Wyndham Goldie discussing the invention of political broadcasting after the War, and Olive Shapley on social documentaries in the 1930s and Woman’s Hour in the 1950s.

Each member of staff was invited to talk frankly about their entire career – the programmes they made, the people they worked with, the creative high-points and low-points, the rows, the social and political changes that shaped their work. For nearly half-a-century, the entire collection was available only to the BBC’s own programme-makers – and even then, under strict conditions. But in 2016, I began a project at the University of Sussex, and working with the BBC, to get the recordings digitised, catalogued, and brought together in one easily-accessed place. If you want to take a look for yourself, it can be found online at ‘Connected Histories of the BBC’.

There, you can access more than 450 interview recordings and transcripts with people ranging from David Attenborough to Hugh Carleton-Greene, from Mark Tully to Annie Nightingale. There’s lots of stuff about the BBC, of course. But because broadcasting touches every facet of life, there are also hundreds of remarkable insights into British political life since the 1920s, the ebbs and flows of social change, the arts, celebrity culture, international relations. As the great broadcasting historian Asa Briggs once said, the history of broadcasting is in one sense ‘the history of everything else’.

*

When it came to putting together my own account D-Day, there were five interviews from the oral history collection which – when combined with material from the written archives – allowed me to piece together events minute-by-minute and from several different angles.

There was Frank Gillard, one of the BBC’s first war correspondents. He talked about how by June 1944 the Corporation had learned from the mistakes it had made earlier in the conflict. One of his fellow correspondents, Richard Dimbleby, had been caught-out accidentally misleading radio listeners about recent battles in North Africa after relying too heavily on over-optimistic briefings from the British Army instead of going to the front and seeing what was happening for himself. It was one of the incidents that led to the creation of the BBC’s own ‘War Reporting Unit’.

There was also Malcolm Frost, who had been in charge of the new Unit. Since he was seconded to both MI5 and General Eisenhower, the commander in charge of the entire D-Day operation, Frost had intimate knowledge of the invasion plans. In his oral history interview, he talks about how the BBC trained its newly-appointed reporters for D-Day, how the Corporation worked with the Allied forces to ensure that its reporters would be in the right place at the right time to make the Channel crossing without giving the slightest clue to the enemy about what was about to happen, and how they hoped to get their dispatches back to London.

As British, Canadian, and American troops moved en-masse through the English countryside to get to their secret embarkation points on the south coast, they were watched by Susan Ritchie, a young clerk for the BBC’s Monitoring Service, who was billeted in the Berkshire village of Pangbourne. In her oral history interview, she gave a wonderful account of watching her hostel slowly fill-up with jittery war correspondents, some of them jumping into a swimming pool to see if their portable recorders were water-proof (they weren’t). Meanwhile, back in Broadcasting House in London, a young duplicating clerk, Mary Lewis, described being taken away from fire-watch duty on the roof to secretly print-off details of the invasion plan and the schedule of programmes the BBC intended to broadcast on the Home Service as soon as dawn broke.

Then, finally, there was a gripping account from the BBC’s chief announcer, John Snagge, who, thanks to Mary Lewis’s efforts, has a copy of the official news of the invasion in his hands the night before and is locked in a studio under armed guard, counting down the time until 09.32 when he’s allowed go on air and let an eager world know that Allied forces were now fighting for their lives on the beaches of Normandy.

So, the BBC’s written archives allowed me to plot the hard facts. But it was these five oral history interviews that took me into spaces and captured moments and feelings that would never feature in the official record. They provided not just a bald chronicle of events: they conjured up a vivid sense of what it was like to be there at the time – the mixed atmosphere of excitement and foreboding, the shredded nerves, the life-or-death need for accuracy and discretion, the feeling of being in on the birth of a brand new era in war reporting.

*

I still don’t count myself an ‘oral historian’, if only because I think of recordings like these as just one of several ‘sources’ that help us to make sense of the past. Even so, dipping into the BBC’s collection of interviews is now something I do automatically whenever I begin a research project.

Obviously, the collection helped hugely when writing my book, The BBC: A People’s History. As I started out, I knew the last thing I wanted was to produce a breathlessly condensed version of the vast multi-volume accounts that had already been written by Asa Briggs. My own, slimmer, narrative needed to be far more selective. Yet I was dealing with an organisation that’s broadcast well in excess of 11 million programmes, employed tens of thousands of people in hundreds of different locations, and generated many miles of archived documents through its daily activities. With so much needing to be left out, what on earth could I do to cast the BBC in a fresh light?

It was the oral history recordings that gave focus to my use of the BBC’s vast written archives.

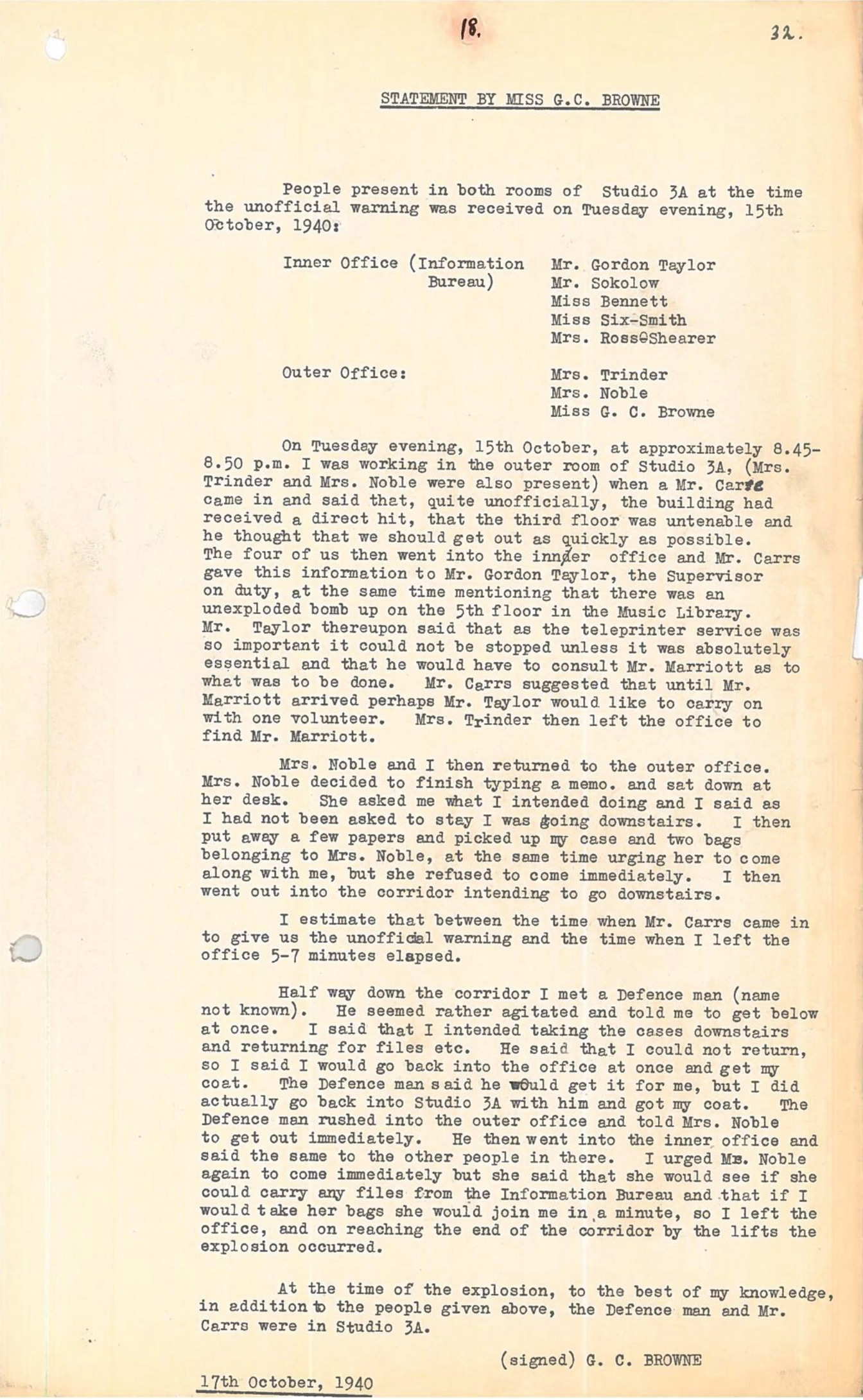

They worked in one of two ways. First, when multiple interviews mentioned the same story, I realised I had to take more seriously certain moments that might originally have seemed rather marginal to the BBC's history. For example, I found a very striking number of interviews referring to the bombing of Broadcasting House during the London Blitz of 1940. It clearly had a profound effect on how members of staff thought of their role during the war – and so it encouraged me to dig out more details of the event from the written record. Among the documents I found was this statement by Miss G C Browne, one of several witness accounts taken from those who were working near Studio 3A when the 500lb bomb crashed into the building.

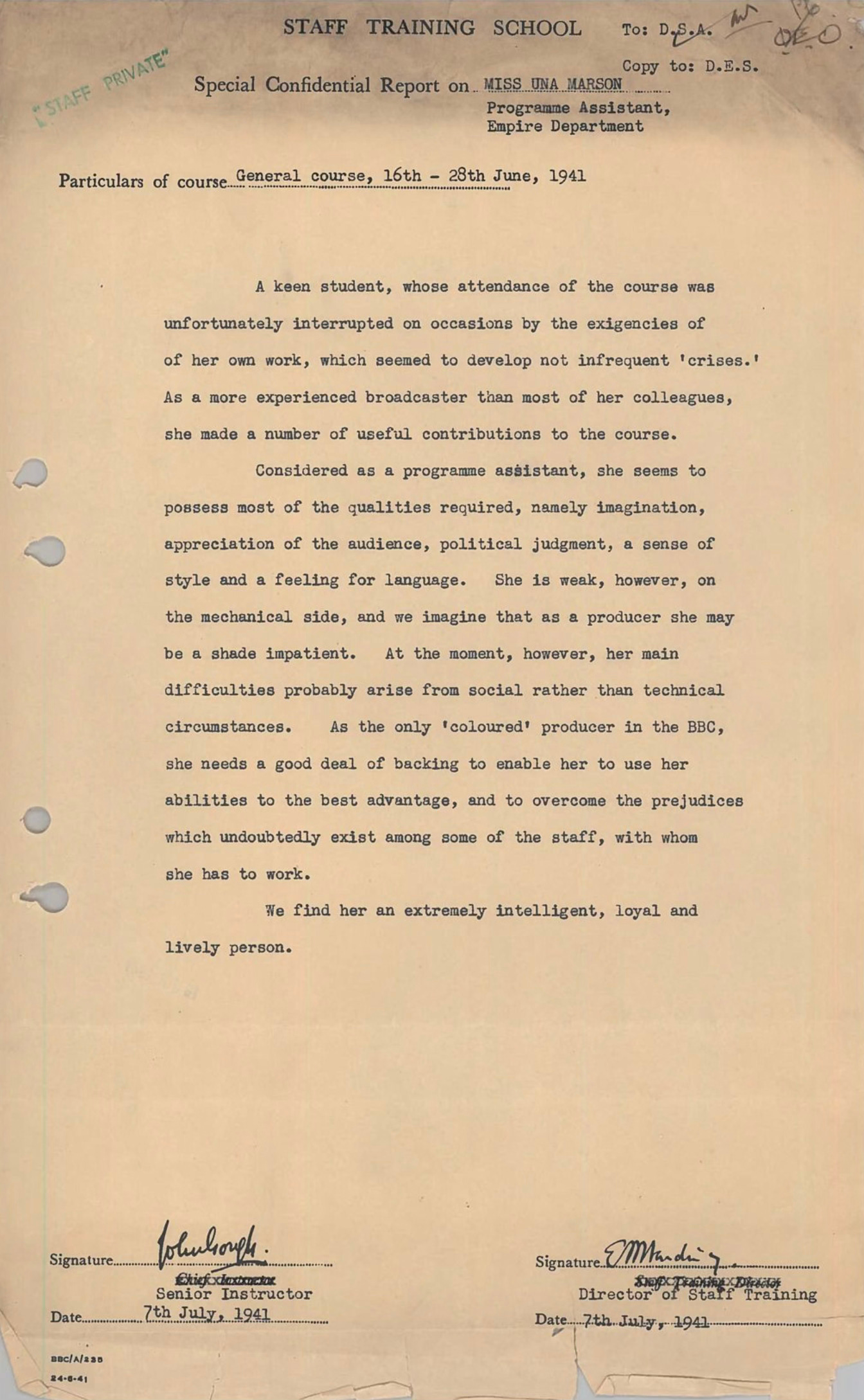

Second, there were sometimes frustrating gaps in the BBC’s oral history collection, which required me to search the written archives in order simply to fill them in. How wonderful it would have been if there was an interview with the Jamaican poet Una Marson, notable as the first programme producer from a Caribbean background to be appointed to the BBC, when she joined just before the outbreak of war. Yet there are very few accounts in the oral history that even discuss issues of identity or the experiences of people such as Marson. Recovering her extraordinary story – including both the high esteem in which senior managers held her and the petty racism she evidently experienced from colleagues – could only be done through another trip to the written archives, where, fortunately, I came across documents such as this, a ‘confidential report’ from 1941:

It was the BBC’s oral history recordings that also gave me the subtitle for the book: ‘A People’s History’. Those three words weren’t there at the beginning. But when they emerged in discussions with my publisher half-way through the process, they started to make sense of what I’d already been doing, only semi-consciously.

Perhaps I already had at the back of my mind the voice of that great expert on Imperial Spain, John Elliott. He once wrote that the task of the historian was ‘to enter imaginatively into the life of a society remote in time and place, and produce a plausible explanation of why its inhabitants thought and behaved as they did.’

While the BBC may not be a society ‘remote in time and place’, it’s certainly always been more than a faceless institution, a factory production-line churning out units of radio and television on demand. I began to think of it as an organism, a living, creative community stuffed full of people who’ve thought deeply - and argued passionately - about their craft. With a lifetime of radio listening and TV viewing behind us, we already know a great deal about what they achieved: with Elliott’s advice in mind, I felt I was able - tentatively, imperfectly - stumble towards knowing just a little more about WHY they did what they did – and what, in their view, the BBC was actually FOR?

In one of her Reith Lectures on the nature of story-telling in historical fiction, Hilary Mantel pointed out that from history ‘proper’ we get to know what our protagonists do, and from historical novels we get to know ‘what they think and feel’. But with the oral history interviews collected by the BBC, we historians can also sometimes reach into the interior worlds of past lives and experience that moment – to quote Mantel – when ‘what is enacted meets what is dreamed, where politics meets psychology, where private and public meet.’

‘The BBC: A People’s History’ was, then, my attempt to humanise the Corporation’s story. Those personal snapshots had a cumulative purpose. I hoped that they would show that public service broadcasting is something that’s been shaped and re-shaped over the past century by thinking, feeling, fallible individuals – flesh-and-blood people, with passions, prejudices, and ideals. The BBC is not – or at least, not yet – a machine.

I also hoped that, having revealed at least something about why the BBC’s inhabitants ‘thought and behaved as they did’, I would provoke a response from readers that goes beyond the absorption of new facts about favourite programmes or landmark events. Researching the book was an emotional process for me as a writer: one notices that among all the failures and mistakes, there was almost always a sincerity of purpose – a fierce desire to do some good in the world. More than anything else, I wanted readers to share in an extraordinary century of service.

As the great 19th Century historian Lord Macaulay wrote, sometimes ‘History has to be burned into the imagination before it can be received by the reason.’

Those archival documents - what insight they give into how staff think! A bomb upstairs - but carry on filing 😄 Admirable aplomb 😁 Lovely background on the human side of the BBC - the oral history archive sounds invaluable. Wish the ABC and other public broadcasters had thought to record their staff - such important social history.

A fascinating read. Thank you.